Surviving the crises that come with growth

Fast growing companies can often be chaotic places to work.

As workloads increase exponentially, approaches which have worked well in the past start failing. Teams and people get overwhelmed with work. Previously-effective managers start making mistakes as their span of control expands. And systems start to buckle under increased load.

While growth is fun when things are going well, when things go wrong, this chaos can be intensely stressful. More than this, these problems can be damaging (or even fatal) to the organization.

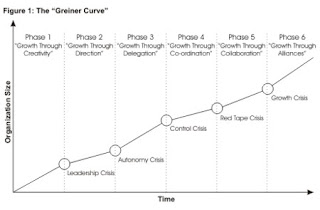

The "Greiner Curve" is a useful way of thinking about the crises that organizations experience as they grow.

By understanding it, you can quickly understand the root cause of many of the problems you're likely to experience in a fast growing business. More than this, you can anticipate problems before they occur, so that you can meet them with pre-prepared solutions.

Understanding the Theory

Greiner's Growth Model describes phases that organizations go through as they grow. All kinds of organizations from design shops to manufacturers, construction companies to professional service firms experience these. Each growth phase is made up of a period of relatively stable growth, followed by a "crisis" when major organizational change is needed if the company is to carry on growing.

Dictionaries define the word "crisis" as a "turning point", but for many of us it has a negative meaning to do with panic. While companies certainly have to change at each of these points, if they properly plan for there is no need for panic and so we will call them "transitions".

Dictionaries define the word "crisis" as a "turning point", but for many of us it has a negative meaning to do with panic. While companies certainly have to change at each of these points, if they properly plan for there is no need for panic and so we will call them "transitions".Larry E. Greiner originally proposed this model in 1972 with five phases of growth. Later, he added a sixth phase (Harvard Business Review, May 1998). The six growth phases are described below:

Phase 1: Growth Through Creativity

Here, the entrepreneurs who founded the firm are busy creating products and opening up markets. There aren't many staff, so informal communication works fine, and rewards for long hours are probably through profit share or stock options. However, as more staff join, production expands and capital is injected, there's a need for more formal communication.

This phase ends with a Leadership Crisis, where professional management is needed. The founders may change their style and take on this role, but often someone new will be brought in.

Phase 2: Growth Through Direction

Growth continues in an environment of more formal communications, budgets and focus on separate activities like marketing and production. Incentive schemes replace stock as a financial reward.

However, there comes a point when the products and processes become so numerous that there are not enough hours in the day for one person to manage them all, and he or she can't possibly know as much about all these products or services as those lower down the hierarchy.

This phase ends with an Autonomy Crisis: New structures based on delegation are called for.

Phase 3: Growth Through Delegation

With mid-level managers freed up to react fast to opportunities for new products or in new markets, the organization continues to grow, with top management just monitoring and dealing with the big issues (perhaps starting to look at merger or acquisition opportunities). Many businesses flounder at this stage, as the manager whose directive approach solved the problems at the end of Phase 1 finds it hard to let go, yet the mid-level managers struggle with their new roles as leaders.

This phase ends with a Control Crisis: A much more sophisticated head office function is required, and the separate parts of the business need to work together.

Phase 4: Growth Through Coordination and Monitoring

Growth continues with the previously isolated business units re-organized into product groups or service practices. Investment finance is allocated centrally and managed according to Return on Investment (ROI) and not just profits. Incentives are shared through company-wide profit share schemes aligned to corporate goals. Eventually, though, work becomes submerged under increasing amounts of bureaucracy, and growth may become stifled.

This phase ends on a Red-Tape Crisis: A new culture and structure must be introduced.

Phase 5: Growth Through Collaboration

The formal controls of phases 2-4 are replaced by professional good sense as staff group and re-group flexibly in teams to deliver projects in a matrix structure supported by sophisticated information systems and team-based financial rewards.

This phase ends with a crisis of Internal Growth: Further growth can only come by developing partnerships with complementary organizations.

Phase 6: Growth Through Extra-Organizational Solutions

Greiner's recently added sixth phase suggests that growth may continue through merger, outsourcing, networks and other solutions involving other companies.

Growth rates will vary between and even within phases. The duration of each phase depends almost totally on the rate of growth of the market in which the organization operates. The longer a phase lasts, though, the harder it will be to implement a transition.

Tip:This is a useful model, however not all businesses will go through these crises in this order. Use this as a starting point for thinking about business growth, and adapt it to your circumstances.

Using the Tool

The Greiner Growth Model helps you think about the growth for your organization, and therefore better plan for and cope with the next growth transitions. To apply the model, use the following steps:

Based on the descriptions above, think about where your organization is now.

Think about whether the organization is reaching the end of a stable period of growth, and nearing a 'crisis' or transition. Some of the signs of 'crisis' include:

People feel that managers and company procedures are getting in the way of them doing their jobs.

People feel that they are not fairly rewarded for the effort they put in.

People seem unhappy, and there is a higher staff turnover than usual.

Ask yourself what the transition will mean for you personally and your team. Will you have to:

- Delegate more?

- Take on more responsibilities?

- Specialize more in a specific product or market?

- Change the way you communicate with others?

- Incentivize and reward you team differently?

By thinking this through, you can start to plan and prepare yourself for the inevitable changes, and perhaps help other to do the same.

Plan and take preparatory actions that will make the transition as smooth as possible for you and your team.

Revisit Greiner's model for growth again every 6-12 months, and think about how the current stage of growth affects you and others around you.